Why Your Brain, Not Your Password, is the Biggest Security Vulnerability

Introduction: The Weakest Link

In the world of cybersecurity, there is a saying that keeps Chief Information Security Officers awake at night: “Amateurs hack systems; professionals hack people.”

You can have the most expensive firewalls, biometric scanners, and 256-bit encryption protecting your digital life. But none of that matters if someone calls you, pretends to be from your bank, and politely asks you to open the door.

This is Social Engineering. It is not a technical exploit; it is a psychological one. It is the art of manipulation, a confidence trick updated for the digital age. While we obsess over strong passwords, cybercriminals are obsessing over human nature. They are studying your fears, your desires, and your cognitive biases.

This article will not just tell you what social engineering is. We will dive deep into the psychology of deception to understand why smart, rational people fall for scams—and how you can harden your mind against these attacks.

Part 1: The Psychology of Deception (Why We Fall for It)

To understand how a scammer works, you have to stop thinking like a computer scientist and start thinking like a behavioral psychologist. Social engineers exploit the “bugs” in our hardware—the human brain.

Our brains have evolved over millions of years to make quick decisions for survival. Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman describes two modes of thought:

- System 1: Fast, instinctive, and emotional (e.g., reacting to a sudden noise).

- System 2: Slower, deliberative, and logical (e.g., solving a math problem).

Social engineering attacks are designed specifically to hijack System 1 and bypass System 2. The moment you stop to think critically (System 2), the scam fails. Therefore, the attacker’s primary goal is to keep you in an emotional, reactive state.

Here are the key psychological triggers weaponized against you:

1. The Amygdala Hijack (Fear and Urgency)

The amygdala is the part of the brain responsible for the “fight or flight” response. When we perceive a threat, the amygdala takes over, literally shutting down the pathways to the prefrontal cortex—the part of the brain responsible for logic and reasoning.

- ** The Attack:** “Your account has been compromised! All funds will be frozen in 10 minutes unless you verify your identity.”

- The Psychological Effect: Panic induces a temporary state of cognitive decline. You aren’t stupid; you are chemically incapacitated by adrenaline. By creating artificial urgency, the scammer ensures you don’t have time to verify the claim.

2. Authority and Compliance

Since childhood, we are conditioned to obey authority figures: parents, teachers, police officers, and doctors. This conditioning is deeply ingrained.

- The Attack: An email from the “CEO” asking for a wire transfer, or a call from the “IRS” or “FBI.”

- The Psychological Effect: This exploits the Milgram Experiment principle. Most people feel extreme discomfort disobeying a direct order from a perceived authority. Scammers use professional jargon, official logos, and authoritative tones to trigger this compliance reflex.

3. Reciprocity (The “Quid Pro Quo”)

Sociologist Robert Cialdini identified reciprocity as a key weapon of influence. Humans have a burning desire to repay favors. If someone does something nice for us, we feel indebted.

- The Attack: A “friendly IT support” person calls and says, “Hey, I noticed your internet is slow. I can fix that for you quickly, just need you to install this patch.”

- The Psychological Effect: Because they offered “help” first, you feel rude refusing their request for access. This is often used in “Tech Support Scams.”

4. The Dopamine Loop (Greed and Curiosity)

Dopamine is the neurotransmitter of desire and reward. It drives us to seek out new information and rewards.

- The Attack: “You have won a $1000 Amazon Gift Card! Click here to claim.” or “See who is secretly in love with you.”

- The Psychological Effect: This targets the brain’s reward system. The promise of a high reward for low effort (clicking a link) releases dopamine. This is the same mechanism that makes gambling addictive. Even if you suspect it’s a scam, the “what if it’s real?” curiosity is a chemical urge.

5. Social Proof and Trust

We look to others to determine correct behavior. We trust people who are “like us.”

- The Attack: A scammer compromises your friend’s Facebook account and sends you a link: “Is this you in this video? OMG!”

- The Psychological Effect: You trust your friend, so you trust the link. The “Halo Effect” bias makes us assume that if the source is good (our friend), the content must be safe.

Part 2: The Arsenal of the Social Engineer

Now that we understand the psychology, let’s look at the specific tools and techniques used to exploit these biases.

1. Phishing: The Dragnet

Phishing is the most common form of social engineering. It involves sending mass fraudulent communications (usually emails) that appear to come from a reputable source.

- The Mechanism: Fake invoices, password reset requests, or shipping notifications.

- The Trap: They often use “typosquatting” (e.g.,

security-google.cominstead ofgoogle.com) to fool your eyes.

2. Vishing (Voice Phishing): The Con Artist

This is phishing over the phone.

- The Mechanism: The caller uses ID spoofing to make it look like the call is coming from your bank or a local number.

- The Danger: Voice creates a stronger emotional connection than text. A skilled “visher” can improvise, answer your doubts, and pressure you in real-time. They often use background noise (like a busy call center) to add authenticity.

3. Smishing (SMS Phishing)

Attacks delivered via text message or apps like WhatsApp, Telegram, or Viber.

- The Mechanism: “Your package delivery failed. Click here to reschedule.”

- The Danger: People trust text messages more than emails. We are used to treating SMS as personal and urgent.

4. Pretexting: The Long Game

Pretexting involves creating a fabricated scenario (the pretext) to obtain information. It requires more research than phishing.

- The Scenario: A scammer might call posing as a survey conductor. “We are doing a survey on banking satisfaction. What is your mother’s maiden name? What was the name of your first pet?”

- The Trap: These seem like innocent security questions, but they are actually the answers to your “Forgot Password” challenges on sensitive accounts.

5. Baiting

Baiting relies on the victim’s greed or curiosity.

- The Physical Bait: Leaving a USB drive labeled “Executive Salaries 2025” or “Confidential” in a company parking lot.

- The Trap: An employee picks it up and plugs it into a work computer out of curiosity. The drive installs malware instantly.

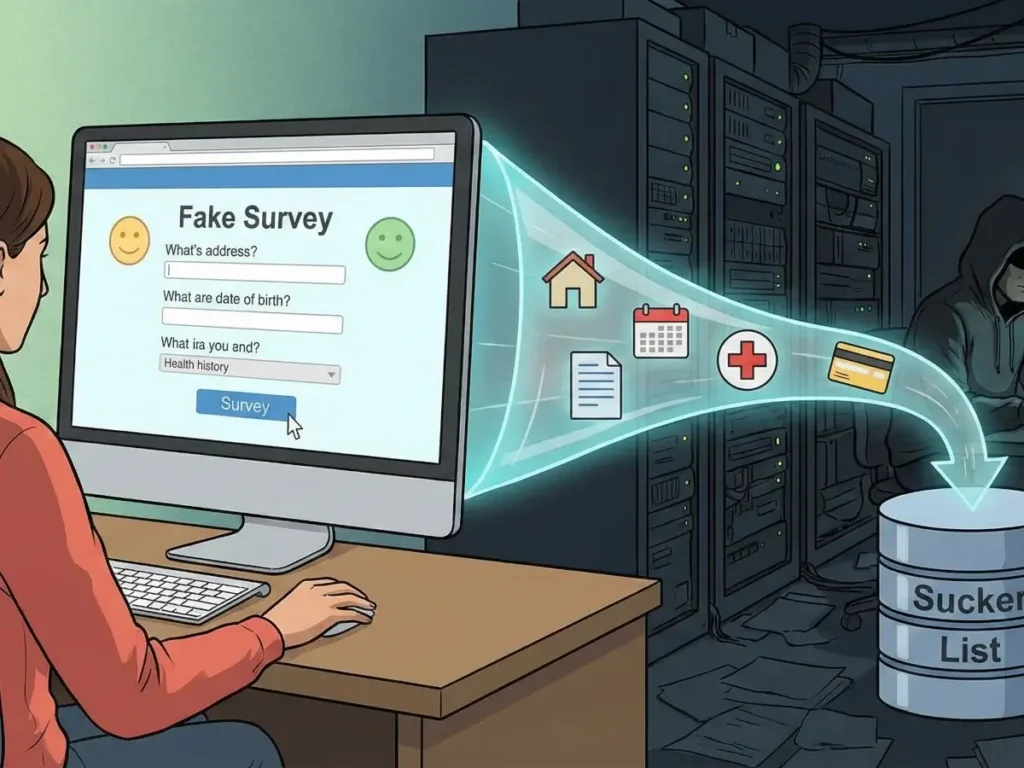

Part 3: The “Paid Survey” Trap: A Case Study in Data Mining

Since we are discussing online safety, we must address a specific niche of social engineering: Fake Paid Surveys.

Websites promising “easy money” for filling out forms are often not market research firms—they are data harvesting operations for social engineers.

How the Scam Works:

- The Hook: “Earn $50 for a 10-minute survey.” (Greed/Dopamine trigger).

- The Qualification: To “qualify,” you must provide your full name, address, date of birth, and phone number.

- The Deep Dive: The survey asks specific questions: “Who do you bank with?”, “Do you own cryptocurrency?”, “What is your medical history?”.

- The Payoff (for them): You are eventually “disqualified” or earn a few cents, but the scammer now has a Fullz (a slang term for a full package of your identity info).

The Result: Two weeks later, you receive a Vishing call. The scammer knows your name, address, and which bank you use. Because they know so much, you believe they are legitimate. The survey didn’t steal your money directly; it gave the attackers the ammunition to steal your life savings later.

Part 4: Digital Hygiene – How to Harden Your Mind

You cannot patch your brain like software, but you can install “mental firewalls.”

1. The Zero Trust Model

Adopt the cybersecurity principle of Zero Trust: Never trust, always verify.

- If you receive an unexpected call from your bank, hang up. Dial the number on the back of your card.

- If an email asks for a password, it is a scam. Legitimate companies never ask for passwords via email.

2. Break the OODA Loop

Military strategists use the OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act). Scammers try to rush you through this.

- The Defense: Stop and Breathe. When you feel panic or urgency, force a pause. Tell the caller: “I need to verify this. I will call you back.” A legitimate representative will agree. A scammer will get aggressive.

3. Information Minimalism

The less the internet knows about you, the harder you are to hack.

- Do not share your phone number on public social media.

- Be wary of “Quizzes” on Facebook (e.g., “Which Star Wars character are you?”). These often harvest profile data.

4. Technical Safety Nets

Since we are human and make mistakes, use technology as a backup:

- MFA (Multi-Factor Authentication): This is your strongest defense. Even if a social engineer tricks you into giving a password, they cannot access your account without the second factor (an app code or hardware key).

- Password Managers: Use them. If you use a unique password for every site, a breach at a sketchy survey site won’t compromise your bank account.

The Hidden Economy of “Paid” Surveys (Data Mining)

The “Product” is You: How Surveys Harvest Your Identity

When you sign up for a dubious paid survey site, you might think you are trading your time for money. In reality, you are trading your Personally Identifiable Information (PII) for pennies. This is known as malicious Data Mining.

Legitimate market research firms (like Nielsen or Swagbucks) are interested in consumer trends. Scam survey sites, however, are interested in building a “dossier” on you. They operate on a simple premise: Reconnaissance. Before a hacker can rob you, they need to know who you are, what you own, and what you fear.

The “Pre-Qualification” Loophole

Have you ever noticed that before you can take a survey worth $2.00, you have to answer 20 “screening questions”?

- “Do you own a home?”

- “What represents your household income?”

- “Do you suffer from any of the following chronic illnesses?”

- “Who is your mobile service provider?”

You answer honestly, hoping to qualify. At the end, the screen says: “Sorry, you do not qualify for this survey.”

The Trap: You didn’t get paid, but they kept the answers. This is a calculated theft of data. By answering those questions, you have just filled out a profile that tells a scammer exactly how to attack you later.

Weaponizing the Data: The “Sucker List”

In the dark corners of the internet, this data is aggregated and sold. Lists of people who respond to online money-making offers are known as “Sucker Lists.” These lists are segmented by vulnerability:

- The Medical Segment: If you indicated you have diabetes or heart trouble, your data is sold to scammers running “Miracle Cure” schemes or fake insurance fraud rings.

- The Financial Segment: If you listed a high mortgage or debt, you will be targeted by “Debt Relief” cold callers or predatory loan sharks.

- The Family Segment: By asking about your family structure (“Do you have children under 18?”), scammers gain the ammunition for Virtual Kidnapping scams—where they call you claiming to have your child, using the specific details you provided in a survey weeks ago to make it sound real.

Key Takeaway: A survey asking for your ZIP code is normal. A survey asking for your mother’s maiden name, exact street address, or medical history is a reconnaissance operation.

The Psychology of Micro-Payments (The Confidence Trick)

The “Loss Leader” Strategy

One of the most dangerous myths in online safety is: “It can’t be a scam because they actually paid me.”

Scammers understand the business concept of a “Loss Leader.” A supermarket sells milk at a loss to get you into the store to buy expensive wine. Similarly, a fraudster will pay you $1.00 to gain your trust, intending to steal $100.00 later. This is a classic Confidence Trick.

Building the Trust Loop

When you receive that first small payment (via PayPal or a gift card), a chemical reaction happens in your brain. Your skepticism vanishes. You think, “This system works! It’s legit!” This small payout disarms your critical thinking (System 2 thinking) and engages your greed and excitement (System 1 thinking).

Once you trust the platform, you invest more time. You spend weeks clicking ads, filling out forms, and watching videos. Your virtual balance grows to $500. You feel productive and successful.

The “Withdrawal Fee” Trap (Advance Fee Fraud)

This is the climax of the scam. When you finally try to withdraw your $500 earnings, the trap springs. You receive a notification:

“To process your payout of $500, we require a one-time verification fee of $49.99 for tax purposes/ID verification/server costs.”

Or:

“Upgrade to ‘Gold Status’ for $100 to unlock instant withdrawals.”

Because they already paid you $1.00 in the past, you believe them. You think, “I pay $50, I get $500. That’s a $450 profit.”

The Reality: You send the $50 “fee.” The $500 never arrives. Then they ask for another fee. They will keep milking you until you realize you’ve been conned. The “earnings” on the screen were just pixels—fake numbers on a web page controlled by the scammer.

Rule of Thumb: Legitimate employers and market research companies pay you. You never, under any circumstances, have to pay money to get your paycheck. If you have to pay to get paid, it is a scam. 100% of the time.

Digital Hygiene – The Ironclad Defense Playbook

To survive in the modern internet, you need to practice Digital Hygiene. Just as you wash your hands to prevent biological viruses, you must adopt specific habits to prevent digital viruses and social engineering attacks.

1. The Principle of Zero Trust

The internet was built on trust; the modern internet requires Zero Trust. This mindset shift is your first line of defense.

- The Concept: Treat every incoming email, SMS, phone call, and website as malicious until proven otherwise.

- In Practice: If you receive an email from “PayPal” saying you received money, do not believe the email. Do not click the link. Open a new browser tab, type

paypal.commanually, log in, and check your notifications there. - The Mindset: Paranoia is not a weakness; it is a firewall for your brain. Verification is the only antidote to deception.

2. Multi-Factor Authentication (2FA/MFA)

Passwords are dead. In an era of massive data breaches, assume your password has already been stolen.

- The Shield: 2FA adds a second layer of defense. Even if a hacker has your password (from a fake survey site breach), they cannot login without the second key.

- Hierarchy of 2FA:

- Good: SMS codes (Better than nothing, but vulnerable to SIM Swapping).

- Better: Authenticator Apps (Google Authenticator, Authy). These generate codes locally on your device.

- Best: Hardware Security Keys (YubiKey). Physical USB keys that must be touched to grant access.

- Action Item: Enable 2FA on your email, banking, and social media accounts immediately.

3. URL Inspection: Reading Digital Street Signs

Phishing sites survive because people don’t read URLs (web addresses). A URL has a strict hierarchy, and scammers try to confuse you with visual tricks.

- The Structure: The “Domain” is the text right before

.com,.org,.net, etc. - The Scam:

support-google-security.com- Here, the domain is

support-google-security. Anyone can buy this for $10. It is NOT Google.

- Here, the domain is

- The Real Deal:

support.google.com- Here, the domain is

google.com. Thesupportpart is a subdomain. Only Google ownsgoogle.com.

- Here, the domain is

- The Hover Technique: Never click a “Download” or “Login” button blindly. Hover your mouse cursor over the link. Look at the bottom left corner of your browser. Does the destination match what you expect? If the email says “Amazon” but the link says

bit.ly/5x7z9, do not click.

4. Critical Thinking: The “Too Good To Be True” Filter

Social engineering exploits greed and desperation. Your own critical thinking is the final barrier.

- The Reality Check: Why would a stranger on the internet pay you $100 for 5 minutes of work? The minimum wage is far lower. If it were that easy, everyone would do it.

- The Assessment: High Reward + Low Effort = High Probability of Scam.

- The Pause: When you feel excitement (“I won!”) or fear (“I’m blocked!”), STOP. Take your hands off the keyboard. Count to ten. Call a friend and explain the situation. Saying it out loud often reveals how ridiculous the scam sounds.

Conclusion

Social engineering is a tax on our trust. It exploits the very traits that make us human: our desire to be helpful, our fear of consequences, and our curiosity.

You don’t need to be a paranoid recluse to stay safe, but you do need to be a skeptic. In the digital age, your attention and your trust are currencies. Do not spend them easily.

Remember: If an offer sounds too good to be true, it’s a scam. If a threat feels too urgent to be real, it’s manipulation. Pause, verify, and stay safe.