In the vast universe of mathematics, few concepts are as simple to define yet as impossibly complex to master as prime numbers. They are often called the “atoms of mathematics” because every integer greater than 1 is either a prime itself or can be built by multiplying primes together.

This article explores what prime numbers are, the complex challenge of factorization, and the mysterious patterns governing how they are scattered across the number line.

1. What is a Prime Number?

At its core, the definition is simple. A prime number is a natural number greater than 1 that has exactly two distinct positive divisors: 1 and itself.

- Examples: 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17…

- Composite Numbers: Numbers that can be divided by numbers other than 1 and themselves (e.g., 4, 6, 8, 9).

- The Special Case: The number 1 is neither prime nor composite; it is a unit.

The Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic

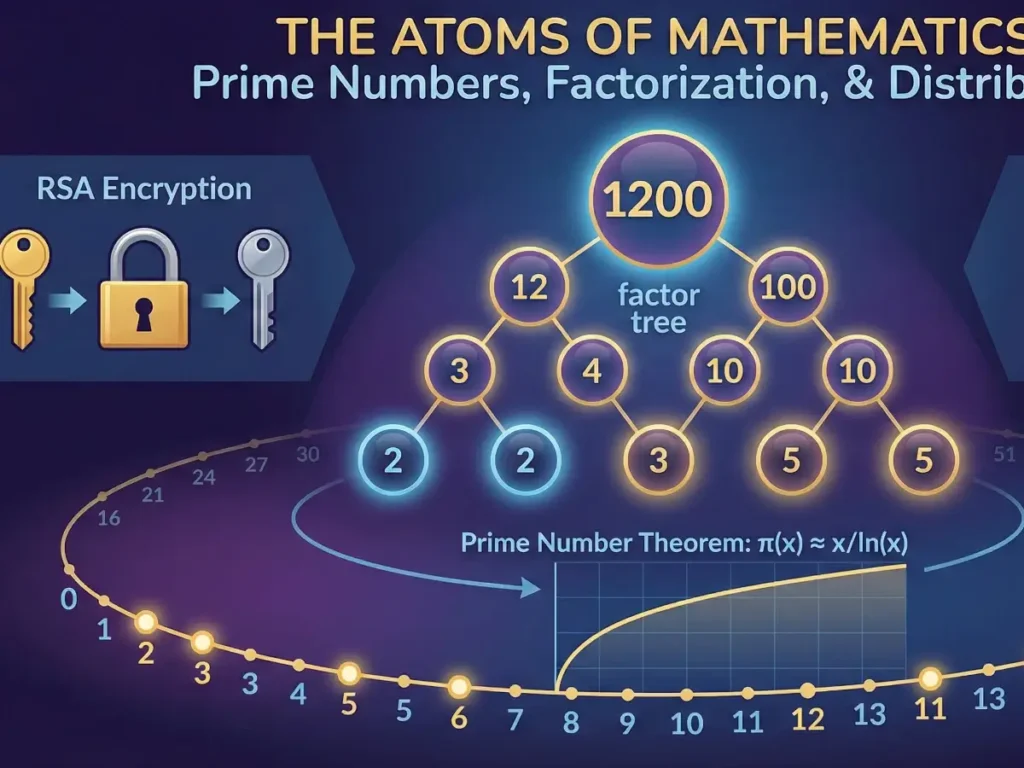

The reason primes are called “atoms” is due to the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic. This theorem states that every integer greater than 1 is either a prime itself or can be represented as the product of prime numbers in a unique way (ignoring the order of the factors).

For example:

$$1200 = 2^4 \times 3 \times 5^2$$

No matter how you try to break down the number 1200, you will always end up with four 2s, one 3, and two 5s. This uniqueness is the bedrock of number theory.

2. Prime Factorization: The Hard Problem

Integer factorization is the decomposition of a composite number into a product of smaller integers. If these integers are restricted to prime numbers, the process is called prime factorization.

The Asymmetry of Arithmetic

There is a distinct asymmetry in mathematics that serves as the foundation for modern cybersecurity:

- Multiplication is easy: If you take two massive prime numbers and multiply them, a computer can calculate the result instantly.

- Factorization is hard: If you take that result and ask a computer to find the original two prime numbers, it is an incredibly difficult task.

For small numbers, factorization is trivial.

$$35 = 5 \times 7$$

However, for a number with 200+ digits, finding the prime factors can take supercomputers hundreds or even thousands of years. This difficulty is what protects your credit card information online (specifically in RSA encryption).

3. The Distribution of Prime Numbers

If you look at a list of prime numbers, they appear to occur randomly.

- 2, 3, 5, 7 (Gap of 2)

- 7 to 11 (Gap of 4)

- 11 to 13 (Gap of 2)

- …

- 1,000,003 to 1,000,033 (Gap of 30)

As numbers get larger, prime numbers generally become less frequent (they “thin out”). However, predicting exactly where the next prime will appear is one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in mathematics.

The Prime Number Theorem

While we cannot predict the exact location of primes, we can predict their density. The Prime Number Theorem describes the asymptotic distribution of prime numbers among the positive integers.

It states that the number of primes less than or equal to a real number $x$, denoted as $\pi(x)$, is approximately equal to:

$$\pi(x) \approx \frac{x}{\ln(x)}$$

Where $\ln(x)$ is the natural logarithm of $x$. This formula tells us that as you go further down the number line, the probability of a random integer being prime drops, following a specific logarithmic curve.

The Riemann Hypothesis

No discussion on the distribution of primes is complete without mentioning the Riemann Hypothesis. Proposed by Bernhard Riemann in 1859, it is considered the most important unsolved problem in pure mathematics.

In simple terms, Riemann found a geometric connection to the distribution of prime numbers using something called the Riemann Zeta Function. If the hypothesis is proven true, it would imply a very strict “order” to the apparent chaos of prime number distribution, allowing us to estimate the count of primes with unprecedented accuracy.

4. Why Does This Matter?

Beyond the beauty of pure mathematics, primes govern the digital world.

- Cryptography (RSA): Public-key cryptography uses a public key (a large number which is the product of two primes) to encrypt data, and a private key (the two specific primes) to decrypt it. Because factoring the large number is computationally infeasible, the data remains secure.

- Hash Tables: In computer science, prime numbers are used in hash functions to distribute data evenly across memory, minimizing “collisions” where two pieces of data try to occupy the same space.

- Biological Cycles: Interestingly, certain species of Cicadas emerge only every 13 or 17 years. Evolutionary biologists believe these prime number life cycles minimize the chance of the Cicadas syncing up with the life cycles of predators.

Conclusion

Prime numbers are the alphabet from which the language of arithmetic is written. From the simple uniqueness of the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic to the complex, mind-bending distribution patterns of the Riemann Hypothesis, primes remain a field of endless discovery. As our computers get faster, our understanding of these numbers must deepen to keep our digital infrastructure secure.