We have explored Prime Numbers and Modular Arithmetic in previous articles. Now, we are ready to combine them to build the actual engine of key exchange.

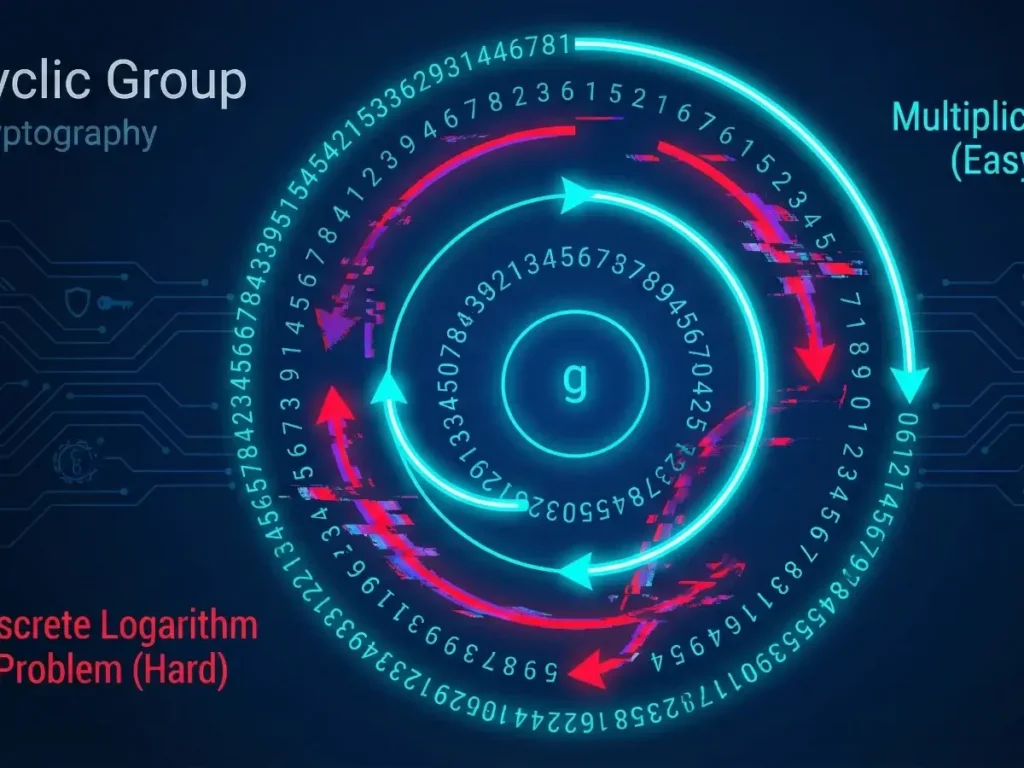

Most modern cryptography (like Diffie-Hellman and ECC) relies on a simple concept: it is easy to mix paint, but impossible to un-mix it. In mathematics, this “mixing” happens inside structures called Cyclic Groups, using a tool called a Generator. The inability to “un-mix” is known as the Discrete Logarithm Problem.

This article explains these three concepts as one cohesive system that secures the internet.

1. What is a Cyclic Group?

In cryptography, we don’t use all numbers. We use a finite set of integers modulo a prime number p. We call this set a “group.”

A group is Cyclic if you can generate every element in the set by taking a single element (let’s call it g) and multiplying it by itself repeatedly.

The “Generator” (g)

The element g is called a Generator (or primitive root). It is the “seed” that grows the entire group.

Example: Modulo 7

Let’s work with the prime p = 7. The available numbers are {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6}.

Let’s test if 3 is a generator.

Step 1: Powers of 3

$$ 3^1 \equiv 3 \pmod 7 $$

$$ 3^2 = 9 \equiv 2 \pmod 7 $$

$$ 3^3 = 27 \equiv 6 \pmod 7 $$

$$ 3^4 = 81 \equiv 4 \pmod 7 $$

$$ 3^5 = 243 \equiv 5 \pmod 7 $$

$$ 3^6 = 729 \equiv 1 \pmod 7 $$

Result:

The outputs are {3, 2, 6, 4, 5, 1}.

Notice that we generated every single number from 1 to 6, just in a scrambled order. This means 3 is a generator, and this group is cyclic.

2. The Discrete Logarithm Problem (DLP)

This is where the security comes from. Let’s look at the equation from the example above:

$$ 3^x \equiv 6 \pmod 7 $$

If I give you x = 3, it is easy to calculate that the result is 6. This is called Modular Exponentiation.

But if I reverse it?

“I have a generator 3 and a result 6. What was the exponent x?”

In standard arithmetic, we solve this with logarithms: \( \log_3(6) \). But in Modular Arithmetic, the numbers bounce around randomly. There is no simple pattern (like a curve) to follow.

The Formal Definition

Given a generator g, a prime modulus p, and a result h, find the integer x such that:

$$ g^x \equiv h \pmod p $$

Finding x is the Discrete Logarithm Problem. For small numbers (like 7), it’s easy. For 2048-bit numbers, it is computationally impossible for all the supercomputers on Earth combined.

3. Real World Application: Diffie-Hellman

How do we use Discrete Logarithm and Cyclic Groups to share a password over the internet without anyone seeing it? This is the Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange.

Imagine Alice and Bob want to share a secret key.

1. Public Setup

They agree on a large prime p and a generator g. Everyone knows these.

2. Private Secrets

Alice picks a secret number a.

Bob picks a secret number b.

3. The Mix (One-Way)

Alice calculates A and sends it to Bob:

$$ A = g^a \pmod p $$

Bob calculates B and sends it to Alice:

$$ B = g^b \pmod p $$

(Note: An attacker sees A and B, but cannot find a or b because of the Discrete Logarithm Problem).

4. The Shared Secret

Alice takes Bob’s public B and raises it to her secret a:

$$ s = B^a = (g^b)^a = g^{ba} $$

Bob takes Alice’s public A and raises it to his secret b:

$$ s = A^b = (g^a)^b = g^{ab} $$

Result:

They both have the same number s ($g^{ab}$), but they never sent it over the network.

4. Python Implementation

Here is a script that finds a generator and demonstrates the difficulty of the discrete log (brute force).

def power(a, b, m):

res = 1

a %= m

while b > 0:

if b % 2 == 1:

res = (res * a) % m

a = (a * a) % m

b //= 2

return res

def discrete_log_bruteforce(g, h, p):

# Finds x such that g^x = h (mod p)

# WARNING: Only works for small numbers!

for x in range(p):

if power(g, x, p) == h:

return x

return -1

# Example

p = 17

g = 3

target = 13

x = discrete_log_bruteforce(g, target, p)

print(f"Discrete Log: 3^{x} = {target} (mod {p})")5. Practice Problems

Test your understanding of Discrete Logarithm and Cyclic Groups.

Problem 1: Is 2 a generator of mod 5?

Set: {1, 2, 3, 4}

$$ 2^1 = 2 $$

$$ 2^2 = 4 $$

$$ 2^3 = 8 \equiv 3 $$

$$ 2^4 = 16 \equiv 1 $$

Result: {2, 4, 3, 1}. Yes, it generated all elements.

Problem 2: Simple Discrete Log

Solve for x: $$ 3^x \equiv 4 \pmod 7 $$

Refer to the table in Section 1.

Answer: x = 4.

Conclusion

The beauty of the Discrete Logarithm and Cyclic Groups lies in their asymmetry. It is a mathematical “trapdoor” that is easy to fall through (exponentiation) but incredibly hard to climb back up (logarithm). This asymmetry is the shield that protects your messages in the digital world.